Chapter 1: The Machine is Satisfied

At the entrance of the Reichsbehörde für Aktenführung und Statistik— which everyone called simply RAS—the line was already formed. We stood in it like obedient punctuation marks.

No one talked. Not because we disliked each other. Because sound carried in places where it shouldn’t.

When my turn came, I took out my Reichsbürgerkarte—the Reich Citizen Card—and slid it through the reader.

The machine swallowed the magnetic stripe and made a single, sterile sound.

PIEP.

ZUTRITT: GEWÄHRT.

ZEIT: 16. Oktober 1985, 06:47.

For a heartbeat I didn’t breathe. I never did, not until the green light came and the turnstile clicked open. It was ridiculous—my card had never failed, not once—but my body didn’t care about statistics. The body is not register-capable. It cared about what happened when cards went silent, or Kartenstumm, which they called it in the office when they thought they were being funny.

If your card went silent, your day was ruined—half a day under fluorescent light, moving from counter to counter, collecting stamps just to prove you still belonged. And then you still had to face your superior and explain why your productivity had been swallowed by procedure.

“Good morning,” the guard said without looking up.

“Good morning,” I answered, and walked through into air that felt artificially regulated—cool and dry, like a museum designed to preserve not paintings but order itself.

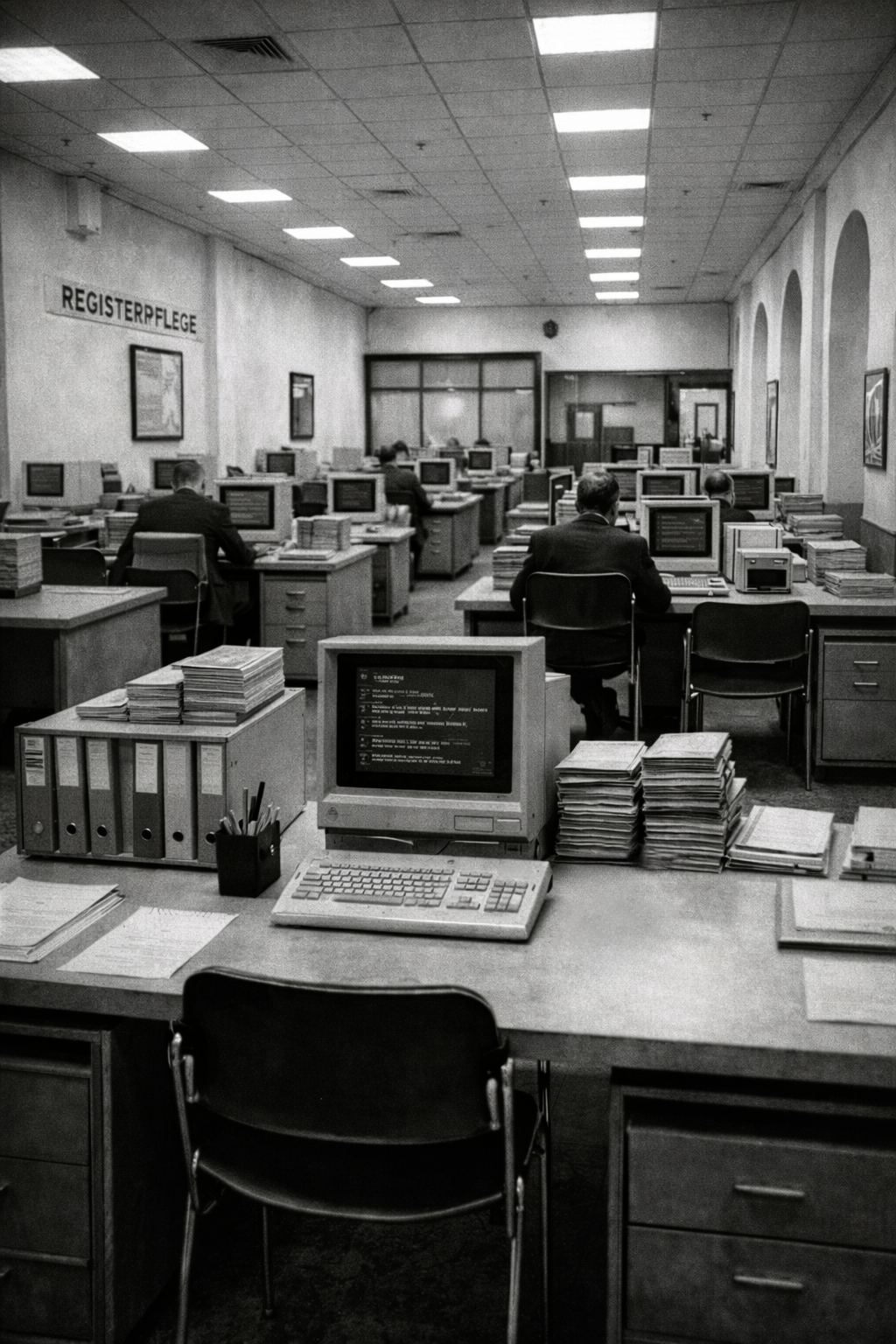

Inside, the corridors of RAS were made to be forgotten. The lighting never changed, the walls never aged, the doors carried identical labels.

I hung my coat, took my place, and logged into my terminal. The screen greeted me with the same line it always did, in the same green letters that made every face look a little sick:

RAS-ZENTRALREGISTER – DATENTREUE IST ORDNUNG.

RAS Central Registry – Data fidelity is order.

I didn’t read it anymore. Not consciously. It was like the smell of toner—part of the room.

Around me, the morning settled into its usual rhythm: the click of keyboards, the soft whirr of barcode scanners, the occasional cough carefully swallowed. On most days, my work had the soothing predictability of assembly. A file arrived as a messy thing, a human thing, full of dates and names and stray words. I made it register-capable. I cleaned it until it fit.

aktenrein, we said. File-clean.

The file is the truth.

A phrase you could repeat without thinking until you realized it was the most dangerous sentence in the Reich.

My inbox tray held three bundles already stamped DRINGEND—URGENT—each tied with string and labeled in the standardized scheme: month, year, Gau code, signature. It was the kind of order the system loved. The kind of order that let you go home at a reasonable time.

Then I saw the new cart by the intake station.

Fresh boxes. Eight of them, stacked neatly. The label on the top manifest read:

URSPRUNG: Reichsgau Oberdonau (Altbestand). Vorgangsgruppe: Gau-Überführung Groß-Wien.

Origin: Reichsgau Oberdonau (legacy holdings). Case group: Gau transfer to Greater Vienna.

The merge was swallowing everything. In the early eighties the Reich had reorganized this region—Niederdonau, Oberdonau, and Vienna fused into a single administrative machine: Reichsgau Groß-Wien—the Greater Vienna Reich District. On paper it was efficiency. In practice it meant every old office, every municipal archive, every dusty registry room had to be emptied into RAS and remade into the new unified record.

That was why I had been selected. Herr Leitner had said it without flattery, as if he were telling me my blood type.

“You don’t panic when things don’t fit,” he’d said. “You make them fit.”

I took a flatbed trolley and began scanning the barcodes. Each box chirped obediently as the system acknowledged it, like a dog returning to heel.

EINGANG BESTÄTIGT.

PRIORITÄT: 1.

EINGANG BESTÄTIGT.

PRIORITÄT: 1.

EINGANG BESTÄTIGT.

PRIORITÄT: 1.

By the third box I was on autopilot.

Then I reached the fourth.

It was thinner, the cardboard worn at the corners, the string tied in a hurry. And where there should have been the standardized label—month, year, Gau code—there was only a single word written in thick black marker:

MAUTHAUSEN

No month. No year. No signature.

Just a name.

My fingers tightened on the handle of the trolley. The feeling was small and stupid—like a chill in a warm room—but it ran up my arms anyway.

Mauthausen.

In the registry, Mauthausen was a location code like any other. A dot on the map. A closed matter. The schoolbooks used different language—Resettlement measures, emergency labor administration, wartime necessities—but the conclusion was always the same. The chapter was closed shortly after the peace of 1942. Everything resolved. Everything normalized.

“Resettlement was harsh but necessary; excesses were punished; peace required order.”

We had written that sentence until it stopped being meaningful.

If I had been asked what I believed, I would have said: I believed the system. The system didn’t allow gaps. The system didn’t allow invalid inputs. If the system said a thing was resolved, it was resolved.

The barcode on the box was there, but crooked, as if someone had slapped it on at the last minute.

I scanned it.

The terminal paused a fraction longer than it should have.

EINGANG BESTÄTIGT.

Quellstelle: Oberdonau / Altbestand / Sonderüberführung.

Hinweis: Kennzeichnung unvollständig.

STATUS: Bearbeitung verpflichtend.

Receipt confirmed. Source: Oberdonau / legacy holdings / special transfer. Note: labeling incomplete. Status: processing mandatory.

Mandatory. Of course it was.

The system never gave you the option of refusal. It was built to remove choice. Choice created gaps.

I rolled the box to my desk and opened it.

There were no neat bundles. No uniform folders. Just mismatched files, some tied, some loose, the paper edges frayed as if they’d been handled too often by people who wanted them to go away.

The first sheet on top was an old requisition form, yellowed, written in that heavy bureaucratic German that always sounded as if it were scolding someone.

Bauanforderung / Materialzuweisung

Construction request / material allocation.

Below it, stamped in faded purple ink, a unit designation. Below that, a date written in careful hand:

14. Februar 1945

For a moment the room blurred. Not because I was shocked in the dramatic way novels described shock, but because my mind performed a quick, silent calculation and found no output.

There was no Mauthausen in 1945. There was only 1942 and then “normalized.” There was peace. There was prosperity. There was the Eternal Führer.

The Reich had names for him that were meant to feel religious, as if the state had always been a church. The most common was the one that appeared on posters and in public speeches: der Ewige Führer.

He had forced the British to accept peace in January 1942. He had secured Lebensraum for a thousand years. He had given the German people order so complete that even now, decades later, the world still obeyed its outline. His greatest success was not conquest but peace. Not war but the end of it.

And because he had given peace, the harsh measures were said to have ended. There was no need for “temporary labor administration” after 1942. That was the official truth.

I swallowed and looked back at the date.

Fourteen February 1945.

The paper was real. The ink was real. It existed in my hands.

The file was the truth.

I forced myself to move. Training took over—my body doing what it had been taught to do with contradictions: reduce them. Periodize them. Make them safe.

I pulled the intake sheet toward me and began creating a new record.

First: location code. The system offered clean options, and I chose the cleanest one it would accept:

Unterbringungsstelle 3 — Accommodation Facility 3.

Second: date.

I typed in 14/02/1945 and, as if to remind me who was in charge, the system snapped back with a sharp error tone.

EINGABE UNZULÄSSIG.

ZULÄSSIGE ZEITFORMATE: Monat / Quartal / Halbjahr.

HINWEIS: Periodisierung erforderlich (HV 12/81).

Input invalid. Allowed time formats: month/quarter/half-year. Note: periodization required (Harmonisierungsvorschrift 12/81).

Of course.

The system did not allow concrete dates. Concrete dates made history too sharp to handle.

I entered I/1945—First Quarter 1945. The red warning vanished. The line turned green.

Then: case type.

The requisition wasn’t subtle. It spoke of capacity increases, additional bunks, more materials. It read like growth. But growth would imply continuation. Continuation would contradict “resolved.” Resolved was non-negotiable.

I navigated the catalog of permissible case types until I found the one everyone used to make bad things sound like administrative residue:

NL-4 – Nachlauf / Abwicklung / Rückführung in Regelzustand

After-run / processing / return to normal operating condition.

A “cleanup” case. A leftover. Something that happened after the ending, not something that extended it.

I selected NL-4.

The system allowed only pre-approved terms and short fields for the description. I typed the sentence I had typed a thousand times:

Unterbringungsanpassung und Versorgungsoptimierung.

Accommodation adjustment and supply optimization.

It was a lie so clean it didn’t even feel like lying. It felt like formatting.

For quantity, I avoided exact numbers—bandwidth categories were safer.

Kapazitätsstufe III

Capacity Level III.

Then the required note:

ZVF-2 – zeitlich zusammengeführt

Time-consolidated.

The record finalized. A calm green confirmation appeared.

REGISTERSATZ: VALID.

STATUS: verwaltungsfähig.

Registry record: valid. Status: administratively viable.

Administratively viable. It was a strange phrase when you thought about it. As if life itself had to be viable in the eyes of a machine.

I looked down at the paper again. 1945. The ink did not become less real because my screen turned green.

I reached for the next file and a shadow fell across my desk.

“Herr—” a voice began, and I turned quickly.

Herr Leitner stood there, hands behind his back, as always. He was close enough that I could smell his aftershave, faint and clinical, like something meant to remove evidence rather than attract anyone.

“How is it going?” he asked in English-accentless German and then repeated, as if correcting himself for my benefit, “How is your progress?”

Leitner did that sometimes—slipped into the Reich’s polished official English for meetings and visiting delegations. Vienna was full of foreigners, full of eyes. RAS liked to think of itself as modern.

“I’ve started,” I said. “The first set is already register-capable.” I used the English term deliberately. It sounded neutral. It sounded safe.

Leitner’s gaze did not go to the paper. It went to the screen. To the green “valid.” “Good,” he said softly. “These boxes need to move quickly. Today.” He paused, then added “And if not today—then certainly by the end of the week.”

“Yes, Herr Leitner.”

He nodded once, then lowered his voice enough that my colleagues would not hear.

“And remember,” he said, “when you are finished with each file, you bring it to Abteilung V – Verwertung und Sicherstellung (Section V – Disposal & Securing). No desk retention.”

We called it just downstairs. Leitner didn’t use the office slang. He used the official name like a warning.

“I know,” I said. I didn’t add: I’ve done it a thousand times.

Leitner’s eyes flicked to the mislabeled box. “Mauthausen,” he said, as if it were a routing code. “You will not leave anything from this box in your drawer. Not for later. Not for tomorrow. Understood?”

Understood. Always understood.

He leaned closer.

“You remember the Brandner case. We don’t repeat that pattern,” he said. My throat tightened before I could stop it. Everyone remembered Brandner. Two small mistakes, two missing handovers to Section V. Two “Fehlerketten”—error chains—triggered by barcodes that didn’t line up.

Brandner had been reassigned to countryside service. Quietly. Efficiently. With no appeal. It was just a regular Versetzung.

“You can’t log a file and destroy it yourself,” Leitner added, as if explaining a safety rule for the hundredth time. “That’s why Section V exists. That’s why the chain-of-custody exists. And as per Rundschreiben V/3–12: no overnight retention.”

“Yes,” I said, and kept my voice even. “I’ll follow the chain.”

Leitner watched me a moment longer than necessary. Then he straightened.

“Good,” he said. “I know I can always rely on you to handle the challenging files.” He walked away.

I stared after him, feeling as if he had left fingerprints on the air. Then I looked back down at the open file. The second document was another requisition.

The third was a list. Names in a column, numbers beside them. It looked like inventory.

Bestand.

I felt a coldness in my stomach that had nothing to do with the building’s controlled climate. Bestand was what you called inventory. Cattle. Steel. Coal. Not names. The safe story in my head whispered automatically, trying to paste itself over the paper.

Resettlement. Emergency measures. Closed chapter.

But the paper didn’t know the safe story. The paper came from a time before this story had been assembled.

I lifted the next sheet. Faded stamp. Handwritten note in the margin. And there, in bureaucratic German, as if it were the most ordinary thing in the world, the document requested:

Anforderung zusätzlicher Kräfte / Zuweisungserweiterung

Additional personnel. Increased assignments. Continuation.

I set the paper down carefully. Somewhere behind me, a barcode scanner chirped. A colleague laughed softly at something on his screen and then remembered where he was and stopped.

The room continued to function. The system continued to accept only what it could accept.

And in front of me, a box with the wrong label contained a story in a year that shouldn’t exist.

I told myself the only thing I could safely tell myself:

This is just a paperwork problem. A formatting problem. A matter of periodization and neutral language. A simple harmonization task for the RAS.

But my hands were already shaking, just slightly, as I reached for the next barcode sticker—because the truth wasn’t the word on the screen.

The truth was that someone, somewhere, had tried to hide these documents badly. And now they were on my desk.

And Herr Leitner wanted them downstairs before the day ended.

I scanned the file into the system anyway.

PIEP.

EINGANG: BESTÄTIGT.

Receipt confirmed.

The machine was satisfied.

The brief pause before the scan, 2.8 seconds, was now part of my record.