Chapter 2: The Approved Route

Lunch in RAS was not a break. It was a scheduled loosening of tension, like unbuttoning a collar one notch.

My terminal clock ticked over to 12:03. The green letters on the screen didn’t change. They never did. The registry did not recognize hunger, only compliance and timestamps.

I saved my work, logged the file status, and placed the Mauthausen folder back into the box with the care you gave to things you didn’t want to touch too long. The barcode sticker on the folder caught the light and looked for an instant like a tiny bandage—an attempt to make something wounded appear orderly.

The cafeteria was two floors up. Downstairs was, by design, in the opposite direction.

I didn’t go to Abteilung V—Section V—yet. I told myself I would. I always did. But hunger was a legitimate reason to delay any thought that might become a problem. And in RAS, even hunger had an approved route.

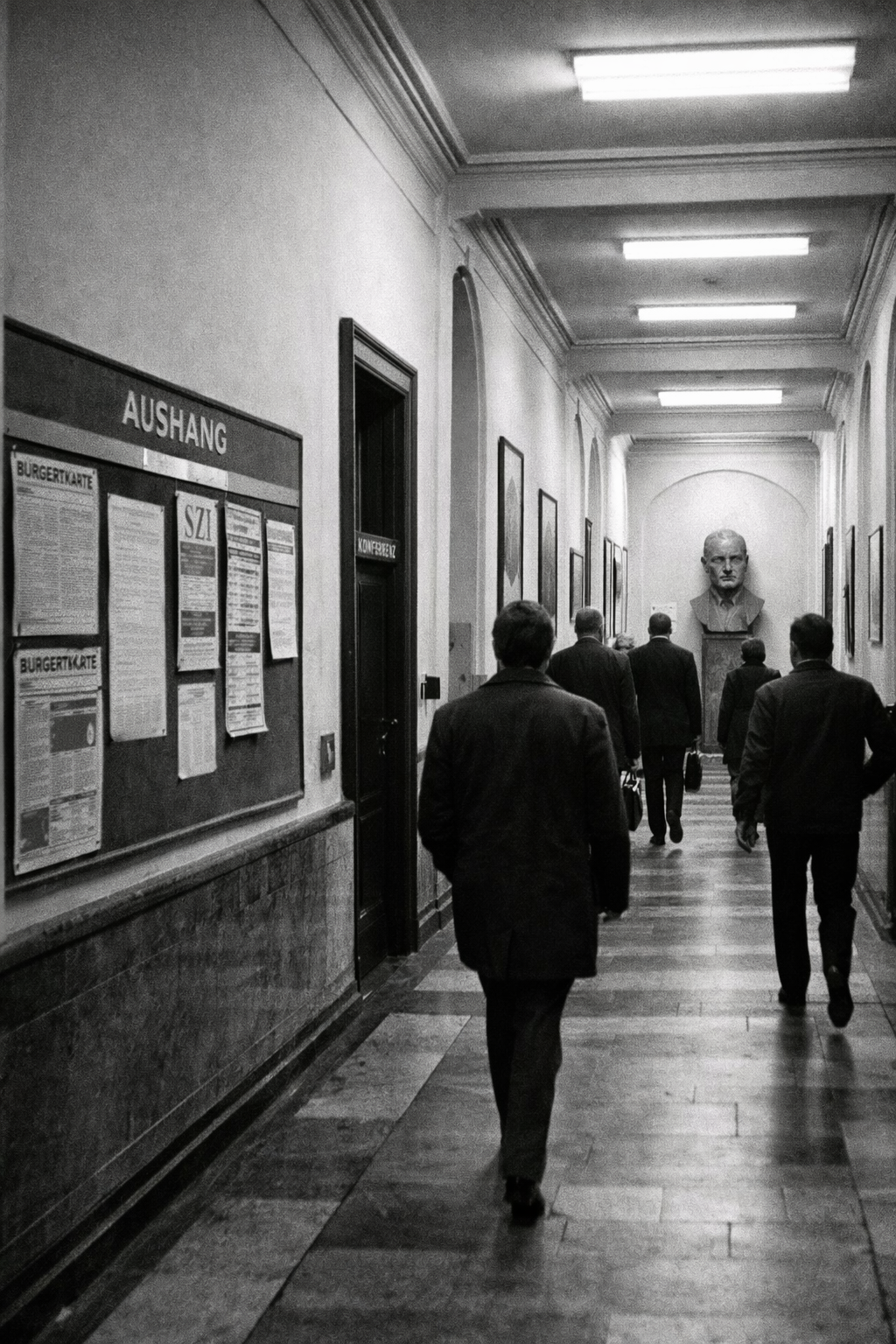

I stood, straightened my collar, and joined the quiet flow toward the stairwell. Around me, chairs scraped back with soft, careful sounds. People moved with practiced efficiency, as if the corridors themselves were timed and any deviation would be registered as an irregularity.

The processing floor was a long strip of pale paint and identical doors. The doors carried their labels in black letters, all the same font, all the same size—because individuality was an aesthetic that suggested looseness.

Eingang — Intake.

Registerpflege — Registry Maintenance.

Schnittstellenstelle — Interface Office.

Auskunft — Information.

The words were harmless. The lives behind them were not.

At the end of the corridor, the wall held a framed slogan, the kind that was so common you stopped seeing it until you needed it.

DATEN SIND PFLICHT.

Data is duty.

Below, smaller:

ORDNUNG IST FRIEDEN.

Order is peace.

I had walked past that frame so many times that my eyes slid over it like water over glass. Only tourists—foreign delegations, conference visitors—paused to read and nod, as if admiring a proverb. For us it was wallpaper. For us it was air.

The stairwell door opened with a hydraulic sigh. Inside, the stairs were concrete and echoed faintly with every step. There were no posters here, no slogans. Just utilitarian space that discouraged loitering.

On the first landing there was a tall window, its glass slightly warped by age. Through it I could see the inner courtyard: gray stone, a few bare trees, two employees smoking quickly beside a “No Smoking” sign, their backs turned to the cameras they pretended weren’t there.

The building had been here long before RAS. It sat near Schottentor like a stone held in a palm: too heavy to throw away, too useful to leave untouched. You could tell by the bones of it—the marble that didn’t match the modern metal, the carved moulding that had been painted over, the way the corridors felt like they had been designed for people who wore uniforms with gold braid instead of plastic badges.

Sometimes, when I climbed the stairs and the sound of my steps bounced back at me, I tried to imagine what it had been before.

A ministry, perhaps—finance, interior, some office that had once moved paper for an emperor instead of a Reich. Or a court archive, storing decrees under wax seals. It had probably been repurposed more times than anyone could count: monarchy to republic, republic to Reich, the old stones made to swear loyalty to whatever flag happened to hang above them.

That was human, I thought. We inherited rooms and gave them new names. We moved our lives into spaces already marked by other lives, and then we pretended the walls had always been ours.

Whatever joys or humiliations had once unfolded here—petty triumphs, quiet cruelties, someone weeping in a corridor after being denied something that mattered—were now only ghosts in a building that did not acknowledge ghosts. The past did not vanish because it ended. It vanished because it was covered, renamed, and eventually walked past without being seen.

We didn’t destroy history, not most of the time. We just built something on top of it until it stopped being reachable.

Two floors later the stairwell spilled into the brighter hallway of the cafeteria level, and the building remembered it was meant to be impressive.

Here the paint was cleaner, the ceiling higher. RAS liked this floor. This was where foreign delegations were guided when they toured the “modern Reich.” This was where the organization pretended to have culture.

At the landing, set into a niche like a relic, stood the bust. A stone head with a sharp nose and a fixed gaze, carved in a style that removed everything fragile and left only authority: der Ewige Führer—the Eternal Führer.

There was no plaque explaining who he was. None was needed. The title was enough. The face was everywhere: on posters, on coins, on official stationery, and on the wall monitors that occasionally played archival footage when the Reich wanted to remind itself that it had been founded by a man and not by a system.

The bust’s eyes did not look at you. They looked through you.

I didn’t slow down. I had passed that niche for years. The mind learned to treat certain things as fixed points of architecture. You didn’t stare at a support beam either.

Beyond the bust, the corridor widened into RAS’s gallery of acceptable memory. Along one wall hung framed landscapes: alpine valleys, clean fields, idealized cityscapes under a sky without smoke. Places that looked like they belonged to a country without secrets.

Between them, spaced like punctuation, were photographs from the Wiener Sicherheitskonferenz 1975—the Vienna Security Conference 1975. Men in suits shaking hands, smiling in the strained way people smiled when they knew the world could end if they misread each other.

The captions were bilingual, because Vienna was a city of foreign eyes.

Stabilität. Verantwortung. Ordnung.

Stability. Responsibility. Order.

Words that meant everything and nothing.

The corridor bent left, and the cafeteria noise began to seep in: the clink of trays, the low murmur of voices. Not loud. Never loud. But different from the hushed clicks of keyboards.

Before the double doors, you had to pass the noticeboards under glass.

They were meticulously arranged. The Reich trusted paper announcements more than whispers.

The first board held a bright flyer about the Reichsbürgerkarte—the Reich Citizen Card—with its cheerful typography and its promise of modernization. A neat diagram showed the card’s functions: transit, healthcare, workplace access, benefits. Everything in one place. Everything convenient.

Below the diagram, a smaller box in stern letters:

MISSBRAUCH ODER UNSACHGEMÄSSE VERWENDUNG IST ORDNUNGSWIDRIG.

Misuse or improper use is an administrative offense.

Progress always came with consequences. The Reich never gave without attaching a chain.

The second board held the newest circular: Rundschreiben 04/84 – Staatszuverlässigkeitsindex (SZI)—Circular 04/84 – State Reliability Index. The public posters called it Zuverlässigkeit—reliability—never loyalty. The word loyalty didn’t appear. It was the kind of omission you learned not to notice.

At the bottom of the circular, the slogans returned like an echo:

Datentreue ist Ordnung. Ordnung ist Frieden.

Data fidelity is order. Order is peace.

The third board held the cafeteria menu, because even food had to be predictable. Monday stew, Tuesday potatoes, Wednesday sausage. A week designed to reduce variation.

I pushed through the doors.

The cafeteria was long and bright, with tables arranged to discourage intimacy. Chairs sat at angles that made it harder to lean close. The ceiling lights were harsh enough that you never forgot you were in a government building.

The smell was boiled vegetables, coffee, disinfectant.

People ate quickly. Lunch was a function. You refueled and returned.

I took a tray, joined the line, and stared ahead. Above the serving counter hung another framed motto:

EINHEITLICHE DATEN – EINHEITLICHES REICH.

Unified data – unified Reich.

Beside it, smaller:

LÜCKEN SIND FEHLER. FEHLER SIND RISIKO.

Gaps are errors. Errors are risk.

The women behind the counter moved with the economy of clerks stamping forms. No wasted motion. No surplus expression.

When it was my turn, I nodded at the sausages, accepted a ladle of thin cabbage and a slice of bread, and moved forward.

At the register, I swiped my Reichsbürgerkarte again. The cashier didn’t look up; her eyes were on the screen that confirmed I was entitled to eat.

PIEP.

A half-second pause—so small I might not have noticed it on any other day.

Then a second sound, sharper and higher, almost like an afterthought.

PIEP.

The display flickered. Green. Normal. The cashier tore off the receipt and pushed it toward me as if nothing had happened.

A receipt with a number.

The machine was satisfied.

I stood there for a moment too long, staring at the strip of paper as if it might explain itself. Two beeps could mean a poor read. A worn stripe. A routine reconciliation. An error that would correct itself if no one touched it. I told myself it was a harmless glitch.

But my mind reached back automatically to the morning’s held breath at the gate, or how I’d hesitated before the document scan, how I’d felt ridiculous for it.

Delays were data, I thought, and immediately hated myself for thinking it.

I forced my feet to move. I carried my tray to a corner table where I could sit with my back to the wall. That was a habit I never admitted was a habit. Around me, conversations hovered in the safe range. Workload. Weather. Transport delays. The museum exhibit someone needed to attend before month-end. A colleague’s child starting school.

No one spoke about history. Not directly. Not in the cafeteria where sound carried and walls had their own kind of hearing.

Outside the windows, the city looked almost ordinary: trams gliding past Schottentor, pedestrians with scarves pulled high, the university buildings standing like they had their own memory of other eras.

Somewhere beneath this bright room and its slogans, there was a place where paper stopped being paper. A place where the past was turned into pulp, or into sealed crates, or into something that no longer belonged to anyone who could name it.

I ate the sausage without tasting it and watched people swipe their cards as if they were paying for lunch rather than confirming their eligibility to eat. Everything in this building ran on the same principle: a human decision, disguised as a neutral procedure.

Someone had designed the stairwells so you didn’t linger. Someone had placed the bust so you couldn’t avoid it. Someone had written the rule that a file could not be destroyed by the same hand that logged it—less to prevent theft than to make responsibility impossible to locate.

By the time I stood up, my tray was empty and my stomach was full. Lunch was logged but the next handover wasn’t. I didn’t look toward the stairwell that led down.